Looking like a stained glass window, this is the remains of the seed pod of one of last summer's garden flowers, Lunaria annua (commonly known as honesty, because the dry seed pods resemble silver coins), magnified around two hundred times and viewed using polarised light.

When honesty seed pods ripen they are flattened and composed of three components. Imagine three large 'coins' joined to each other all around their rims, with the central 'coin' attached to the plant via a stalk. Swelling seeds are attached to the rim of both faces of the central 'coin' via their own slender stalks, visible when sunlight shines through the whole structure.

When the pod dries out and ripens the tensions in the drying, contracting cells of the walls of the 'coins' tear them apart around their rims, so the two outer 'coins' detach and flutter away in the breeze, followed by the winged seeds, leaving the central 'coin' attached to the dead plant and surviving deep into winter.

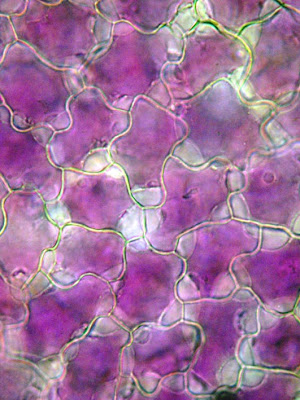

These are the cells of that central, surviving 'coin' magnified about one hundred times and using ordinary white light....

... and these are the dazzling interference colours generated when polarised light is used.

At two hundred times magnification it's clear that the 'coin' is formed from two layers of cells, orientated at different angles, so that the tensions they develop when they dry will twist and distort the 'coin' and help to rip apart the sutures with the outer 'coins'.

At four hundred times magnification you can clearly see the pores through the thick cell walls which were the plasmodesmata - the channels of communication between the cytoplasmic contents of one cell and the next, while the whole structure was still alive and the seeds were still developing.